Officials planning project for nearly 1,400 sites in East Maui in hopes of saving native birds

December 13, 2022

Mosquitoes incapable of reproducing would be released by drone and helicopter at nearly 1,400 locations across Maui forests under a widespread effort to curb the insects that are spreading deadly avian malaria amongst native birds.

Officials offered an in-depth glimpse of how they plan to deploy the incompatible mosquitoes across nearly 65,000 acres of state, federal and private lands as part of a project that’s been discussed for years but grown more dire in recent months amid efforts to keep the dwindling bird populations alive. The project, if successful, has the potential to suppress the southern house mosquito population by 90 percent or more, according to a draft environmental assessment for the project published Thursday in “The Environmental Notice.”

More than 30 species of forest birds known as Hawaiian honeycreepers have gone extinct, and many of the remaining 17 species are considered at risk.

Avian malaria, which is caused by a parasite spread by the invasive southern house mosquito, is the primary cause of the honeycreepers’ decline, as they have little resistance to the disease, and most cannot survive infection.

“Until recently, honeycreepers were able to persist in high elevation forests where it is too cold for mosquitoes and the avian malaria parasite to reproduce,” the report said. “Recent climate changes have allowed mosquitoes and associated avian malaria to start invading these upper elevation forests on Maui, killing native forest birds in their last remaining locations.”

At least two endangered bird species in East Maui, the kiwikiu (also known as the Maui parrotbill) and the akohekohe, are expected to become extinct within two to 15 years if avian malaria is left unchecked. Both have declined by more than 70 percent over the last two decades, and scientists estimate that there are currently fewer than 200 kiwikiu and fewer than 2,000 akohekohe still in the wild — all in East Maui.

It’s why state and federal officials are proposing the mosquito control measures that would suppress East Maui populations of the southern house mosquito, the only insect that transmits avian malaria in this area.

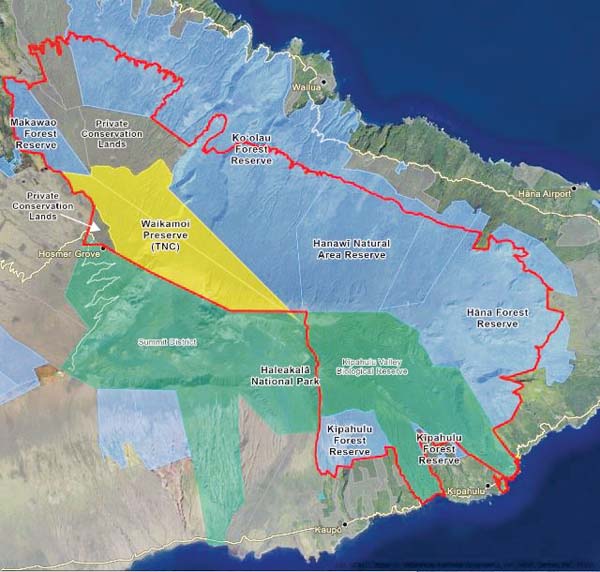

The National Park Service and state Department of Land and Natural Resources worked together to identify the areas for the mosquito control project, targeting the ranges of the forest birds as well as areas downslope from the birds’ ranges that may serve as high-density mosquito breeding grounds.

The project area spans 64,666 acres, including 37,989 acres of DLNR forest and natural area reserves; 12,042 acres of NPS land; adjacent lands privately managed in a conservation easement by The Nature Conservancy (8,606 acres), East Maui Irrigation Co. (4,409 acres) and Haleakala Ranch (393 acres); and 1,227 acres of Mahi Pono lands managed for conservation.

The agencies pinpointed 1,389 release locations, including 340 in the Koolau Forest Reserve, 262 in the Hana Forest Reserve and 211 in Haleakala National Park, the top three targeted sites.

Efforts would start small: southern house mosquitoes would be reared in a sterile lab from eggs initially collected on Maui. The lab would likely be located at a Mainland facility, at least at the start, and mosquitoes would be transported to Maui. The mosquitoes would be inoculated with a bacteria known as Wolbachia, which naturally occurs in the eggs and sperm of many insect species. When an incompatible strain of the bacteria is introduced to the female mosquitoes, mating is unproductive.

Mosquitoes would be taken into the field in small-scale on-the-ground or aerial releases in the project area, where field teams could keep tabs on the success of the project.

Because most of the project area is inaccessible by ground, releases would primarily be conducted via drones, which would fly about 50 to 100 feet above the tree canopy to release small biodegradable packages designed to open upon contact with the canopy or forest floor.

Proposed release locations would be spaced 1,300 feet apart, so a drone flying at 22 mph would be able to release incompatible mosquitoes at 24 release locations in a 15-minute period, according to the report.

If drones can’t be used, helicopters could be used to release the mosquitoes over a short-term period of up to two months, either through a release device attached to the belly of a helicopter or from a long cable affixed with a device that could allow release of mosquitoes closer to the forest canopy or floor.

A helicopter going at 22 mph could complete 68 to 74 release locations per hour; in six hours of flying, it could cover 412 to 443 release locations.

Officials expect to release anywhere between 50 and 6,000 incompatible mosquitoes per acre per treatment (which would occur up to twice per week) depending on elevation and local temperature and capture data gathered during monitoring.

Releases would continue until southern house mosquito populations are significantly reduced and the status of threatened and endangered forest birds stabilizes, or until new methods of suppressing mosquitoes are developed.

In June, the state Board of Agriculture approved the controlled importation and release of male southern house mosquitoes in Hawaii.

The project would only release male mosquitoes, which do not bite animals or humans, according to the report. Because the invasive southern house mosquito occupies higher elevations and cooler environments than other species of mosquitoes found on Maui, other species of mosquitoes would not expand their ranges as southern house mosquitoes are eliminated, the report said. Southern house mosquitoes are not an important source of food for native bats, birds or other insects in Hawaii, so the project is not expected to impact their feeding habits.

Wolbachia bacteria is already present in many insects in Hawaii and cannot transfer between animals species or to humans.

Both DLNR and NPS are seeking public input on the plans. For more information or to submit comments, visit parkplanning.nps.gov/HALE-mosquito.

To view the full draft environmental assessment, visit planning.hawaii.gov/erp/environmental-notice/ and click on the Dec. 8 edition of “The Environmental Notice.”

* Colleen Uechi can be reached at cuechi@mauinews.com.